Most departments has active field training protocols that recruits must pass after leaving the academy. This means they ride along with the FTO until they are ready to function independently as LEO’s. The specific time line for this depends on FTO daily observation reports during the phases of field training. These begin with close supervision where the trainee does little of the daily work. In the latter phase of training the FTO may pull back and provide intervention only if needed by allowing the trainee to be the lead on all calls.

Officer resilience depends upon solid field training with adequate preparation for tactical encounters, legal and moral dilemmas, and mentoring for long-term physical and mental health. Michael Sefton, Ph.D. 2018

Law enforcement officers begin their careers with all the piss and vinegar of a first round draft pick. This needs to be shaped by supervised field training and inevitably will be effected by the calls for service each officer takes during his nightly tour of duty. Much like competitive athletes, law enforcement officers at all levels exhibit “raw” talents, including leadership abilities and the cognitive skills to go along with them. Moreover, like competitive athletes, these raw abilities have to be honed, refined and advanced through a combination of modeling, coaching and experience in order for the officer to develop the skills needed to improve performance, as well as prepare them for career advancement according to Mike Walker. This important task falls upon the field training officer (FTO) and is a critical phase in probationary police officer’s development. “The FTO is a powerful figure in the learning process of behavior among newly minted police officers and it is likely that this process has consequences not only for the trainee but for future generations of police officers” according to Caldero and Crank (2011). In 1931 the Wickersham Commission found over 80 percent of law enforcement agencies had no formal field training protocols for new officers entering the field of police work described by McCampbell (1987). In 1972, formalized field training protocols were introduced by the San Jose, CA police department that became a national model for post academy probationary field training.

Just before I was promoted to sergeant while working for a law enforcement agency, USCG Vice Admiral John Currier, a friend of mine said to me: “Michael, move up or move out”. I wasn’t sure what he meant by that but given my 9 years as a patrolman, I started to lobby for a promotion to sergeant. The agency at which I worked had little turnover in the middle ranks so I was never sure I would get a chance for promotion.

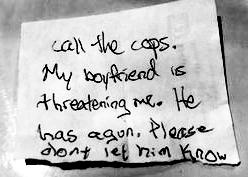

All law enforcement officers should have a career path when they graduate the academy that lays out a career path based on officer interest, career improvement goals, on-going training interests, and agency needs. Training opportunities offer new officers the chance to gain experience in anything from specialized investigations i.e. sexual assault and child abuse, firearms instructor, domestic violence risk assessment to bike patrol and search and rescue. Our chief believed strongly in incident command, active shooter response, and emergency medical technician training. I went on to take the paramedic technician course at a local college in 2011-2012. In many ways my former agency was well ahead of the curve in training opportunities and tactics including use of body worn video cameras, taser training, stop sticks, and individually deployed patrol rifles. I was encouraged by my chief to participate in a research opportunity I was offered in domestic violence homicide from a case in northern Maine, a community much like the one I served. From this research we introduced a risk assessment instrument developed by Jacquelyn Campbell.

The chrysalis for me came in August, 2012 when I was appointed by the Select Board to sergeant at the recommendation of my chief. Before this could occur, I had put in a significant amount of time developing a field training program, domestic violence awareness and lethality assessment protocols, and police-mental health encounter training. I learned the hard way that most police officers do not like working with citizens with mental illness and hate attending training classes on mental health awareness and crisis intervention training. I realized that I needed to become a leader and in order to do so I needed to become better in communicating with the troops and with those up the chain of command. In order to develop leadership I was sent to sergeants school but what I learned was the importance of being a role model for those in training and to teach by doing, teach by example. I also learned that field training is demanding, exhausting work if done with the precision needed to fully socialize the trainee and provide needed modeling while gradually offering greater independence for the trainee.

Field training involves months of practicing ‘what if‘ scenarios, learning the ropes of the police service, use of force, and writing reports. Early in the phase of training the tough discretionary decisions faced by a probationary officer are made by the senior training officer based on prior judgement, experience and what is most prudent for the specific incident and conditions on the ground. “Agencies should thus maintain a greater degree of FTO supervision, not just trainee supervision. Such an effort would go a long way toward improving FTO programming and better informing the needed research base” Getty et al. (2014, pg. 16). Field training is often time limited with special consideration for officers who need additional training in specific skills or personal areas of concern. Some officers are put on career improvement plans and extended field training, when needed, and some probationers are discharged from the agency because of skills or behavior that are not compatible with police work. Law enforcement agencies want active police officers who represent the core beliefs of the agency and individual community needs.

Field training involves months of practicing ‘what if‘ scenarios, learning the ropes of the police service, use of force, and writing reports. Early in the phase of training the tough discretionary decisions faced by a probationary officer are made by the senior training officer based on prior judgement, experience and what is most prudent for the specific incident and conditions on the ground. “Agencies should thus maintain a greater degree of FTO supervision, not just trainee supervision. Such an effort would go a long way toward improving FTO programming and better informing the needed research base” Getty et al. (2014, pg. 16). Field training is often time limited with special consideration for officers who need additional training in specific skills or personal areas of concern. Some officers are put on career improvement plans and extended field training, when needed, and some probationers are discharged from the agency because of skills or behavior that are not compatible with police work. Law enforcement agencies want active police officers who represent the core beliefs of the agency and individual community needs.

Field training has perhaps the most potential to influence officer behavior because of its proximity to the “real” job according to Getty, Worrall, and Morris (2014).

Probationary officers can be taught the how and when of effecting an arrest but the intangible discretionary education comes from FTO guidance and socialization that takes place during the FTO training period. Research has revealed that officers’ occupational outlooks and working styles are affected more by their FTOs than formal “book” training, Fielding, 1988. The selection of who becomes an FTO is not well defined. In a study at Dallas PD probationary trainees were exposed to multiple FTOs over 4 phases (Getty et al. 2014). The study revealed a correlation between new officer behavior – in the 24 months after supervision, as measured by citizen complaints and the FTO group to whom they were assigned. It is conceivable that the results in the study may be due to the relative brevity of training at each phase may have stopped short of instilling good habits or extinguishing bad habits in many new police officers. I have worked in agencies where only the sergeants were the FTO’s by virtue of rank and supervisory acumen long before systematic field training programs were introduced. In Dallas, results showing officer misconduct via high citizen complaints may too have been associated with unprepared FTO’s who were drafted to supervise the trainee and who were not prepared for that role.

“Bad apple” and/or poorly trained FTOs may thus have a harmful influence on their trainees. Getty et al. (2014)

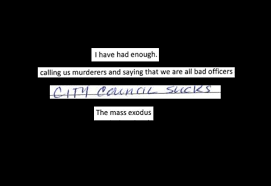

Choosing successful FTO’s is of critical importance for new officer development and for future generations of law enforcement officers. The values espoused by the FTO have enormous impact on the behavior, habits, and professionalism of new police officers. It has been shown that the quality of this training belies post-supervision job behavior and success. Haberfeld (2013) has offered a supportive assessment of the assessment center approach to FTO selection suggesting there are qualities that may be quantified in the selection process. This may be helpful in the selection of FTO’s who are professionally resilient and emotionally hardy as they lead the new probationary officer into his career. If officers are randomly assigned to provide field training without forewarning or preparation this may staunch career growth in the probationary LEO. If this becomes the norm then FTO’s may have provide more of what probationary officers need such as correct values, discretionary wisdom, and perhaps less negative socialization that can lead to embitterment, misconduct, and citizen complaints.

At times of high officer stress when high lethality/high acuity calls are taken the probationary LEO is apt to require greater support and guidance from the FTO. It is during these critical incidents that post hoc peer support and defusing may take place. Training LEO’s should be permitted to openly discuss and express the impressions they experience to calls that may be more violent, and outside of the daily norm for what he or she has been doing. In doing so, the impact of these high stress exposures may be mitigated and emotional resilience may germinate. The responsibility of FTO’s to reassure and invigorate trainee coping skill and mindful processing of critical incidents cannot be under emphasized. FTO’s understand that healthy police officers must be permitted to express horror when something is horrible and feel sadness when something leaves a mark. They will become better equipped in the long run if allowed to fully appreciate the emotional impact that calls for service will elicit in them. The stigma of high reactive emotions from high stress incidents, i.e. homicide or suicide, is reduced when officer share the call narrative and its allow for its normal human response.

Michael Sefton, Ph.D.

2019

REFERENCES

Caldero, M. A., & Crank, J. P. (2011). Police ethics: The corruption of noble cause (3rd ed.). Burlington, MA: Anderson.

Fielding, N. G. (1988). Competence and culture in the police. Sociology, 22, 45-64.

Getty, R, Worrall, J, Morris, R. (2014) How Far From the Tree Does the Apple Fall? Field Training Officers, Their Trainees, and Allegations of Misconduct. Crime and Delinquency, DOI: 10.1177/0011128714545829, 1-19.

Haberfeld, M. R. (2013). Critical issues in police training (3rd ed.). Upper Saddle River, NJ: Pearson.

McCambell, M. Field Training for Police Officers: The State of the Art (1987). DOJ: NIJ, April.